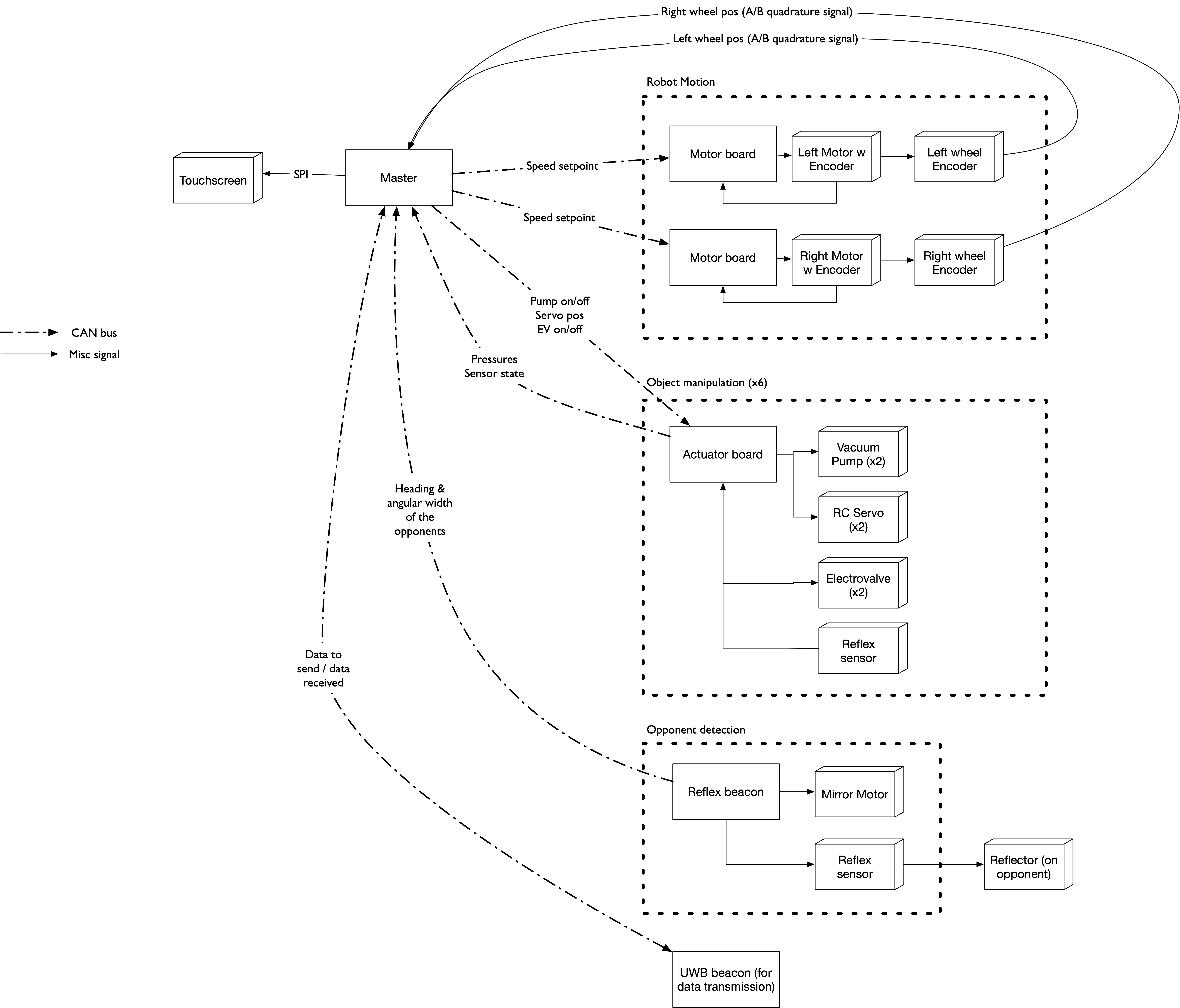

Hardware architecture overview (2020 edition)

The robot is organized around a master board, which is a shield for a Raspberry Pi 4. This board is responsible for most of the high-level tasks in the robot:

- Odometry

- High level control & pathfinding

- Game script

- User interface

The low-level functions are delegated to simpler boards, running microcontrollers. Board exchange messages over CAN bus using the UAVCAN protocol.

- Our motor boards are responsible for PID control of a single motor. In 2020, they are used only for the wheelbase, but they are very generic and can be used for other purposes, e.g. controlling a robot's arm.

- To handle the objects used by the 2020 rules, we chose to use suction cups and vacuum pumps. In order to control those, we designed a specific actuator board. This board also integrates vacuum sensor to detect if an object was correctly taken. An optical sensor allows this board to detect if an object is close. Finally, it can control standard RC servomotors, as we needed those this year.

- The robot detects opponents by using a beacon system based on light reflection. The beacon mast emits a beam of light, which is reflected by a circular catadiopter fitted on each opponent. By rotating the sensor, the Debra platform measures the apparent size of the reflector, which provides an approximation of the distance. This information is then sent back to the master board over CAN.

- The two robots in a team can communicate together and with the lighthouse using UWB radio. To do so, we re-use the modules developed for positioning but only for data transmission.

Why so many boards?

In 2010, we arrived at the conclusion that modular electronics were the best long term solution for the club. That's because our members stay at the club for a relatively long time, compared to a school's club, where a high turnover is expected. That means that we can afford to see in the longer term, even if it is not ready.

We first started with putting one single FPGA in the robot, and our hope was to change the logic inside it depending on what we wanted. For example we could add PWM and encoder channels if we had more motors in the robot. This worked for a while, but the overall pin count in an FPGA is fixed, which limits modularity. Also, programming FPGA is hard and the only engineer doing that in the club had limited time.

In 2015, we decided to go with horizontal scaling: instead of one big controller, put many small ones and connect them with a network. This gives almost unlimited flexibility: "just" add new board to add new capabilities. It allows us to develop new hardware each year, without throwing away everything we did previously.

In 2020, we realized that we were spending too much time writing low level code on the master firmware for things like memory management. The system was complicated and alien, meaning it was hard to onboard new developers. Switching to a Linux platform while still programming in C++ simplified our life, without requiring complex architures (à la ROS) or major rewrites.